ASEAN, or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is an economic union in Southeast Asia made up of ten member states that promotes intergovernmental cooperation and facilitates economic, political, security, military, educational, and sociocultural integration between its members and other Asian countries.

The major goal of ASEAN was to speed economic growth and, as a result, social and cultural development. The promotion of regional peace and stability based on the rule of law and the principles of the United Nations charter was a secondary goal. With some of the world’s fastest-growing economies, ASEAN’s goals have expanded beyond the economic and social sectors.

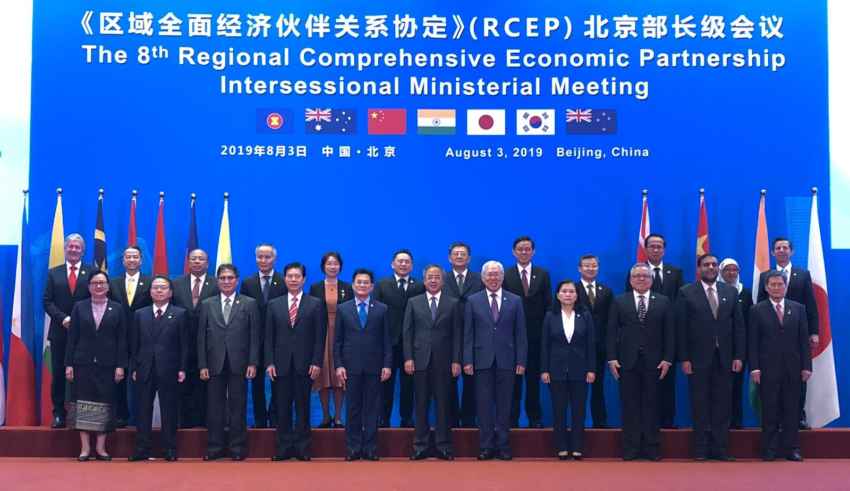

Accordingly, the ten ASEAN Member States (Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, the Philippines, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and Viet Nam) finally signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with five other trading partners – Japan, the People’s Republic of China, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand – during the 37th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit hosted by Viet Nam.

The peculiarities of RCEP’s provisions and what this new structure means for the future of international commerce and investment in the larger Southeast Asia-East Asia-Australasian area are discussed in this piece, since the participating nations in this agreement account for about 30% of world GDP.

Overview of The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a free trade agreement Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, South Korea, and Thailand are among the 15 signatories to the RCEP. Negotiations between the parties began in 2012, with India as a participant until it stepped out in 2019. As of 2020, the 15 member nations account for around 30% of the world’s population (2.2 billion people) and 30% of global GDP ($26.2 trillion), making it the world’s largest trading bloc (Nikkei Asian Review,2020). It is made up of a mix of high-, middle-, and low-income countries It’s also the first free trade deal between China, Japan, and South Korea, Asia’s three largest economies (South China Morning Post,2020).

The Agreement aims to unite and enhance economic operations between the existing ten-member ASEAN trade bloc and five other East Asian nations, including China, Korea, and Japan (known as ASEAN+3), and Australia and New Zealand (known as ASEAN+5) (EU Directorate General,2021). also, The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is one of two “mega-regional” trade accords in East Asia. The other is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which was signed in 2018 and now has eleven signatories: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam (Ibid).

The objectives of the RCEP

The general objectives are outlined in chapter 1 of the Agreement. Article 1.3 provides that (RCEP,2020);

“The objectives of this Agreement are to:

- establish a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial economic partnership framework to facilitate the expansion of regional trade and investment and contribute to global economic growth and development, taking into account the stage of development and economic needs of the Parties especially of Least Developed Country Parties;

- progressively liberalise and facilitate trade in goods among the Parties through, inter alia, progressive elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers on substantially all trade in goods among the Parties;

- progressively liberalise trade in services among the Parties with substantial sectoral coverage to achieve substantial elimination of restrictions and discriminatory measures with respect to trade in services among the Parties; and

- create a liberal, facilitative, and competitive investment environment in the region, that will enhance investment opportunities and the promotion, protection, facilitation, and liberalisation of investment among the Parties.”

The RCEP focuses on facilitating trade in goods and services across Asia in general, as well as exploring more market access liberalization by addressing the standard range of trade themes found in modern trade agreements. However, it was evident from the start of the discussions that the membership constellation, which includes nations with widely diverse degrees of economic growth, would have an impact on the Agreement’s goals (EU Directorate General,2021).

As a result, the Agreement has flexibility and commitments that are distinct. This is exemplified by the number of various tariff schedules (38 in all), with tariff liberalization for some items taking place over extended periods of time (20 years or more), as well as a variety of obligations in terms of service liberalization and investment (Ibid).

The RCEP’s structure and provisions

The Agreement is divided into 20 chapters and spans 510 pages. Chapter 2 (Trade in Goods) follows Chapter 1 (Initial Provisions and General Definitions) and provides requirements for trade in goods. National treatment clause, elimination of customs duties, duty-free temporary admissions, customs valuation, goods in transit, reaffirmation of World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments related to export competition and export subsidies in agricultural products, quantitative restrictions, and import licensing are just a few examples of such obligations.

Over a 20-year period, the parties undertake to lower or abolish customs duties imposed by each member on originating products by about 92 percent. Some tariffs will be eliminated immediately, while others will be phased out over the course of 20 years.

Chapter 3 (Rules of Origin, ROO) determines which goods are originating under RCEP and therefore can benefit from preferential tariff treatment. Also, Advance rulings, rules of origin, customs valuation, customs clearance of goods, risk management, and post-clearance audits are all covered in Chapter 4 entitled as “Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation”. In additions, the next set of chapters covers non-tariff measures (Ibid).

While the scope of the RCEP is significant, the coverage of the Agreement’s commercial flow-promoting clauses falls short. In comparison to the CPTPP, the RCEP is less extensive. As a result, the RCEP’s influence on shaping international economic norms and global regulatory governance is likely to be less than that of the CPTPP. For most of the following key issues of international economic law, the RCEP provides a framework (Mbengue, Schacherer,2021);

- Trade in goods: RCEP does not deliver significant new market access for goods in terms of tariff reduction and elimination. As mentioned before, most RCEP parties already have existing FTAs in force with each other through bilateral or plurilateral agreements (i.e. ASEAN+1 FTAs and the CPTPP).

- Rules of origin: The RCEP provides for certain common rules, such as harmonizing the information requirements and local content standards for businesses to be eligible to the preferential terms of the Agreement. The RCEP is expected to facilitate sup-ply-chain management within the region to a significant extent.

- Trade in services: The RCEP establishes ruled for the supply of services including obligations to provide access to foreign service suppliers (market access), and to grant national treatment and most-favoured nation treatment.

- Investment RCEP’s investment chapter contains traditional investment protection standards. It contains provisions on investment facilitation and prohibits performance requirements on foreign investors. The RCEP does not provide for investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) but includes a built-in work agenda, which will start no later than two years after the Agreement’s entry into force and will consider whether to amend RCEP to include ISDS. This approach seems to reflects a new trend regarding ISDS. Indeed, the very recent conclusion of the negotiations of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between the EU and China (30 December 2020) also includes a commitment by both sides to pursue the negotiations on investment protection and investment dispute settlement within two years of its signature.

- Electronic commerce: The RCEP covers commitments on cross border data flows and provides for a more conducive digital trade environment. It limits the scope for governments to impose restrictions including requirements to localize data (Article 12.14).

- Intellectual property (IP): The RCEP seeks to raise standards of IP protection and enforcement including non-traditional trademarks and a range of industrial designs. RCEP parties, which have not yet done so, commit to accede to international IP treaties (Article 11.9). On geographical indications (GIs), parties must adopt or maintain transparency obligations and due process with respect to its domestic legal framework on the protection of GIs.

- Government procurement: The RCEP parties commit to publishing laws, regulations and procedures regarding government procurement, while cooperation provisions set out a mechanism to facilitate consultation and exchange of information.

Conclusion

The RCEP is the world’s largest trade and investment agreement to date, including over 30% of global GDP (USD 26.2 trillion) and one-third of the world’s population. as a result, the RCEP’s magnitude is exceptional, as it creates the world’s biggest trading bloc (after North America and the EU) and the world’s second-largest investment bloc (after the EU). Accordingly, as it is crucial to address the implications for the International Economic and Investment Law, in this article various aspect of this agreement has been explored.

Bibliography

Nikkei Asian Review, 2020, “India stays away from RCEP talks in Bali”, accessed 10 November 2021<https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade/India-stays-away-from-RCEP-talks-in-Bali>.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership,2020.

South China Morning Post., 2020, “”What is RCEP and what does an Indo-Pacific free-trade deal offer China?”, accessed 10 November 2021< https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3109436/what-rcep-and-what-does-indo-pacific-free-trade-deal-offer >.

EU Directorate General,2021, “Short overview of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)”,

Mbengue, Schacherer,2021, “Systemic Implications of the RCEP for the International Economic Law Governance”, accessed 11 November 2021< https://www.afronomicslaw.org/category/analysis/systemic-implications-rcep-international-economic-law-governance >.

By The European Institute for International Law and International Relations.